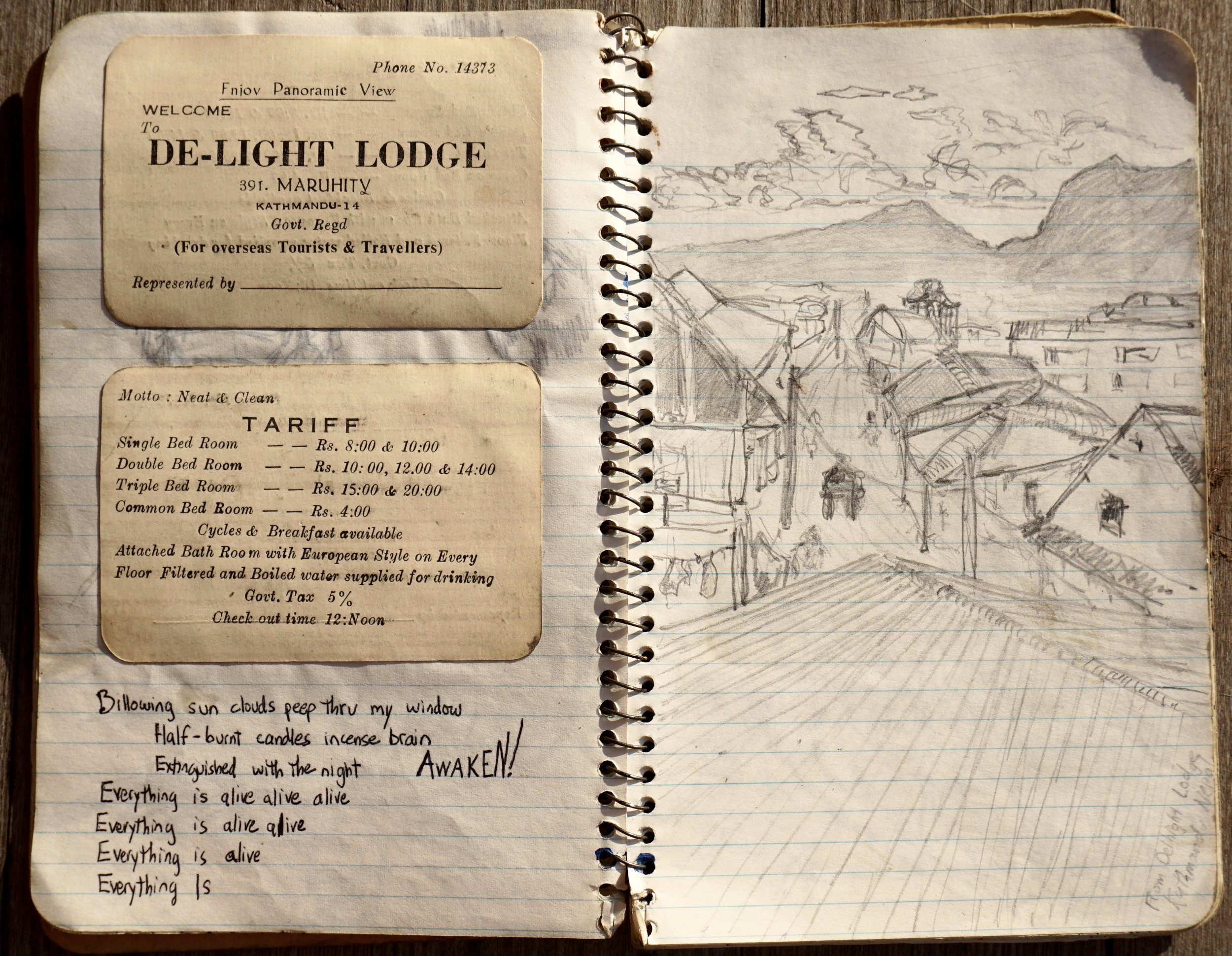

MEMORIES OF NEPAL: TREKKING AND LOCAL JUSTICE.

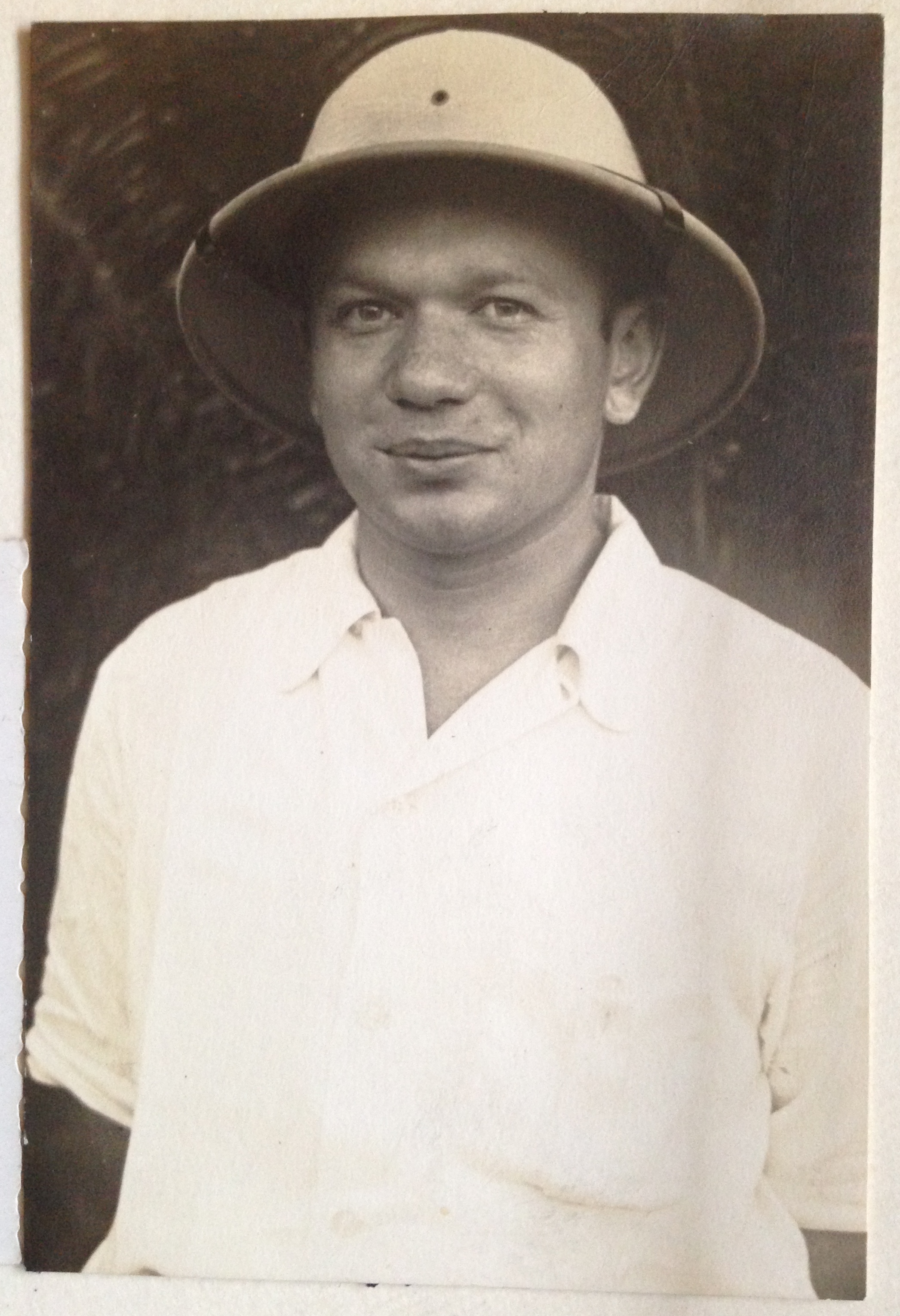

While in Kathmandu in 1982 Terry and I arranged a trek in the Himalayas. Through a tourist agency we hired a crew who would carry our packs, cook our meals, set up and break camp, and lead us on a route near Machhapuchhre in the Annapurna Range, a towering and imposing 24,000 foot mountain rising dramatically from a much lower plateau. Safety was supposedly not an issue--we had heard only positive things--but having a guide not only made for greater comfort but it also was insurance against getting lost in the mountains if we undertook the trek on our own, and even though we were traveling on the cheap it didn’t stretch our budget too much. We were matched up with a Canadian woman and an Australian guy, both about our age, and to attend to the four of us, we were provided with an experienced guide named Ratna, a cook and several porters. We met most of them in Pokhara after a several hour bus ride along winding mountain roads from Kathmandu, and set out the following day.

Day one started out on an inauspicious note. Less than two hours after leaving Pokhara we were walking on a broad path along a fast flowing river when we saw a strapping young Tibetan man, with broad muscled shoulders and glowing skin, lying face down in the water among large boulders. Several people had arrived at the scene. Word spread quickly that he had committed suicide. We were shocked, we were told it was highly unusual, and we walked on, shaken.

The trek was amazing. We walked about 50 miles in 8 days, about 3000 vertical feet per day, sometimes challenging. There were few roads in Nepal at the time and the villages and towns were connected by a vast network of paths. Some paths were broad and flat and could accommodate pack animals, and some were narrow and steep and rocky and only agile humans could navigate them. They wound through forests and small villages and along mountainsides, sometimes with vertiginous views. At one point we passed through a dense miles-long forest of 30-foot rhododendron trees in full bloom.

The larger paths, and even the smaller ones, were essentially foot highways. Streams of people passed by, some carrying unfathomable loads. Most stuff was carried in a sort of giant hemp-like sack with a broad strap that went around the forehead; the weight was borne on the forehead and back and those who carried heavy loads of wood and bags of rice and root vegetables walked stooped toward the ground. Believe it or not we even saw a few porters carrying giant loads of glass-bottled Coca Cola on their backs up to the higher more remote villages. Many walked barefoot in all kinds of weather, though some had hand-me-down sneakers with the laces removed and open just enough to squeeze in their widespread feet that were so terribly cracked and rough. Any romantic notion I harbored that they might be hardened to the pain fell away quickly.

Because transport was so difficult, and because everything had to be hand carried, most products were extremely local. In the course of a few hours of walking you could pass through one village with houses built only of bamboo and grasses and another village further up the mountain in which all the houses were made of stone and stucco. Endless miles of terraced fields turned whole mountainsides into giant avant-garde geometric earthworks best seen from the opposite sides of valleys, and spoke of hundreds of years of back-wrenching work. And we got some spectacular views of high peaks. One morning we awoke very early and climbed about 2500 feet before dawn, rising to about 13,000 feet to see the sun rise between multiple 20,000+ foot peaks and fast moving clouds. I felt like I was dreaming at the top of the world.

Each evening the crew gathered wood and started a fire, cooked rice and cut up vegetables for curry, brewed tea, and set up the tents. Considering our pretty basic standards at the time, it was comfortable. We all got along well. The porters spoke some English, Ratna was mostly fluent, and they were sensitive and gentle, though their lives were anything but. One morning we passed through a town and the cook bought a live chicken for the dinner that evening. The gentleness and loving attention the cook paid to the chicken that day was beautiful. He carried it in his pack on his shoulder and petted its head and cooed to him all day along the path; the chicken seemed calm and content. When it came time to prepare dinner, the cook deftly slit the neck of the chicken, drained the blood, collected it and cooked it separately, an apparent treat. I don't remember any struggle.

On the fourth night of the trek we camped just outside a village with about a dozen small houses, situated on a river. As usual we left our backpacks in the open air outside our tents, this time propped up against a stone wall. When we got up in the morning the packs were gone. Ratna and our crew were in disbelief, and within minutes the whole town was there, arguing. They seemed in shock. "This kind of thing never happens." "Our livelihood depends on the trekkers coming through." They were ashamed for their fellow countrymen and worried that word might spread to avoid the area.

We weren't sure what to do. We had the one set of clothes we had taken off in our tent, our sleeping bags, and luckily our wallets with our passports. Everything else was gone, clothes, first-aid kits, supplies. Ratna discussed the situation with men from the town. A decision was made--without my input--that we would walk 6 hours each way to the nearest police outpost to report the incident; it was considered that important. So I got ready to walk the 12 hour round trip, maybe for nothing. Terry and our Canadian and Australian friends were to stay the day in the village and enjoy lying in the sun and swimming in the river.

We were a sort of a posse. Ratna, one of our porters, a half dozen people from the town where we were robbed, and I started walking in the direction of the outpost. They would ask every person we passed whether they had seen a stolen pack or anything suspicious. About an hour in, someone said he'd seen a guy in unusual clothes just up ahead. Indeed he was wearing my shirt and sneakers. He ran, but the villagers caught up with him, tackled him and roughed him up, with slaps to the face and body and lots of screaming and threatening.

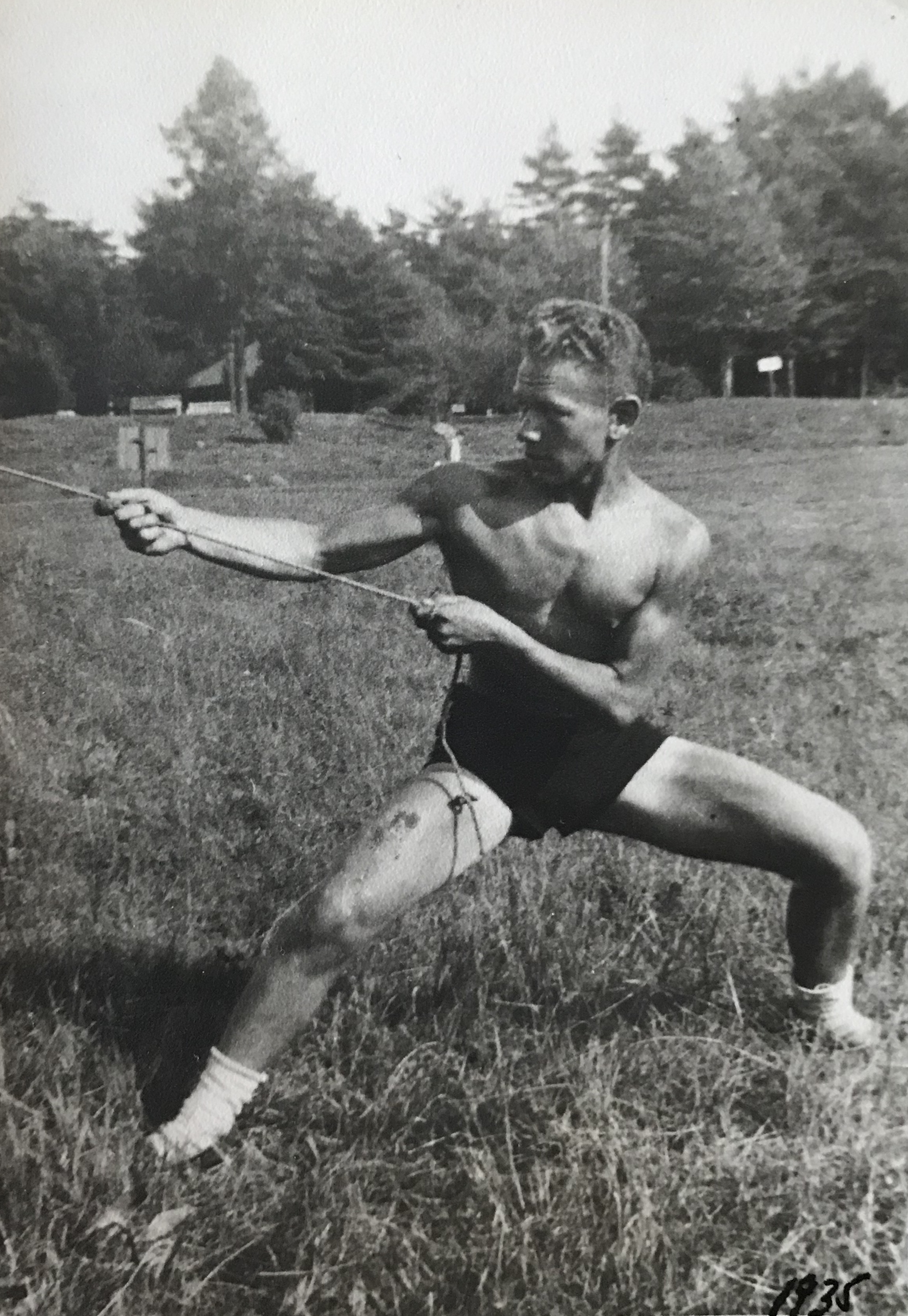

After claiming that he'd bought the stuff from the thief, upon more coercion he finally admitted that he'd taken the packs, but that it had been in the middle of the night and now the goods were spread around to other people. They kept slapping and screaming at him and finally he said that he had stashed the stuff in a bunch of hidden locations that he could take us to. Meanwhile more local villagers joined us; there was a reputation to uphold. For the next 4 or 5 hours, as he led us through miles of remote terrain, we ran and leapt up and down the beautiful terraced hills, 2 or 3 feet at a time, all at high altitude. I happened to be in the best shape of my life at that point, but I was stretched to my physical limit. Absolutely exhausting and rattling. The locals were running and jumping like billy goats and olympic hurdle champs and I was just making it, with blisters and aching knees.

He'd hidden things behind rocks in remote forests, in friends' huts in several villages, in a container buried in the dirt, and it turned out, his mother's house. The "posse", which had grown to about 20 folks by now, physically dragged him up to his village, which consisted of a half dozen bamboo huts and some cleared dirt, found his mother, screamed at her, slapped her on the face numerous times, knocked her to the ground and then started kicking dirt on her. At this point the low-level fear I had felt all day turned to near-panic; how violent would local justice get? Much to my relief they left her on the ground and made the thief apologize, formally, directly to my face. Very intense.

We got almost everything back. The only things gone, if I remember correctly, were a few packs of cigarettes and a couple of Cadbury chocolate bars, all presumably consumed by then, and one pair of Terry's underwear.

The next day we continued our trek. My knees were a bit shaken and sore, but once again we were glorying in the unforgettable beauty of the country and the charm of the people. Perhaps the most bizarre part of the whole episode followed. For the next three days, until our return to Pokhara, hundreds of people coming from every direction asked if we were the victims of the robbery. The news had spread throughout the countryside for many many miles. Locals, porters, trekkers, everyone knew about us. We were briefly famous.