MY FATHER IN WORLD WAR TWO

When I was six years old I discovered my father's world postage stamp album. In it, amidst what seemed like a trove of jewels, was a page of brightly colored stamps from French Guiana showing jungles, natives in dugout canoes, and archers in loincloths drawing back their bows and aiming upward, calmly tensed and poised to shoot. The first time I remember him talking about his wartime experiences was when I asked him about those stamps.

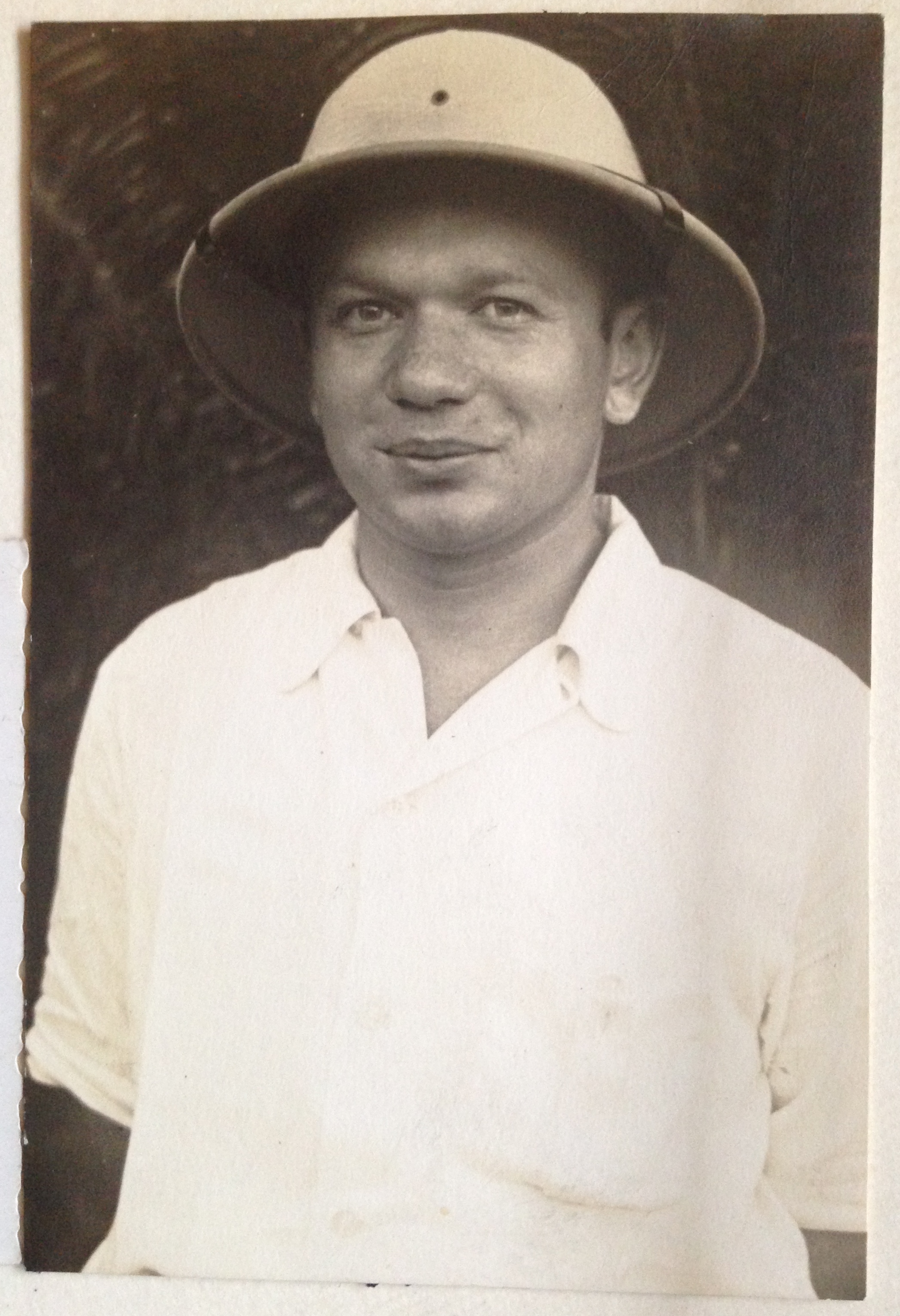

Samuel Malam was, in a way, an embodiment of the American Dream. Born Shmuel Melamedman in 1918 in a town about 40 miles from Kiev, he was a year old when my grandparents fled their home after a horrific pogrom. Their epic journey took them south through eastern Europe to Constantinople, much of it by foot, and from there on to New York City, where they arrived at Ellis Island in 1923, along with a younger son Benjamin who was born along the way. By 1940 my father, who started first grade confused, terrified and not speaking a word of English, had graduated with an architecture degree from NYU, won the prize for the best draughtsman in his class, and had been assimilated into the American melting pot.

In the wake of Pearl Harbor, armed with his recently minted architecture degree, he joined the Seabees, the civilian battalion responsible for military construction, and later signed on with the Navy as Chief Petty Officer. He was shipped out to Trinidad, British West Indies in early 1942 and put to work designing, organizing and directing the building of airbases there. It was thought that the Germans would try to establish military bases in South America and make their way north, eventually attacking the mainland US. As a defense, the Americans started building bases all through the Caribbean and northern South America.

He spent the war years in what he liked to refer to as "the tropics”. Unlike many of his compatriots who served in the European and Pacific theaters, he saw no combat and his life wasn't being threatened. In fact, despite some privations and hardships—being away from his family for the first time, missing his wife-to-be, eating crappy food, and suffering from a constant barrage of heat and humidity, not to mention scorpions and gigantic snakes--as an officer he lived relatively well and he spoke of that time of his life with excitement and nostalgia.

From early 1942 until December 1945, he was sent from outpost to outpost, mostly in Trinidad and French Guiana, but also in Dutch Guiana, Puerto Rico and elsewhere. Sometimes he lived on bases in or near cities and towns, other times in end-of-the-earth wilderness, always directing the clearing of jungles and forests in order to lay down concrete runways and build barracks, offices, munitions storage facilities, and the other infrastructure of air bases. It was his first “real” job, and with it came a sense of authority, the satisfaction of seeing projects go from conception to completion quickly, and the notion that they were doing essential and necessary work to further the war effort.

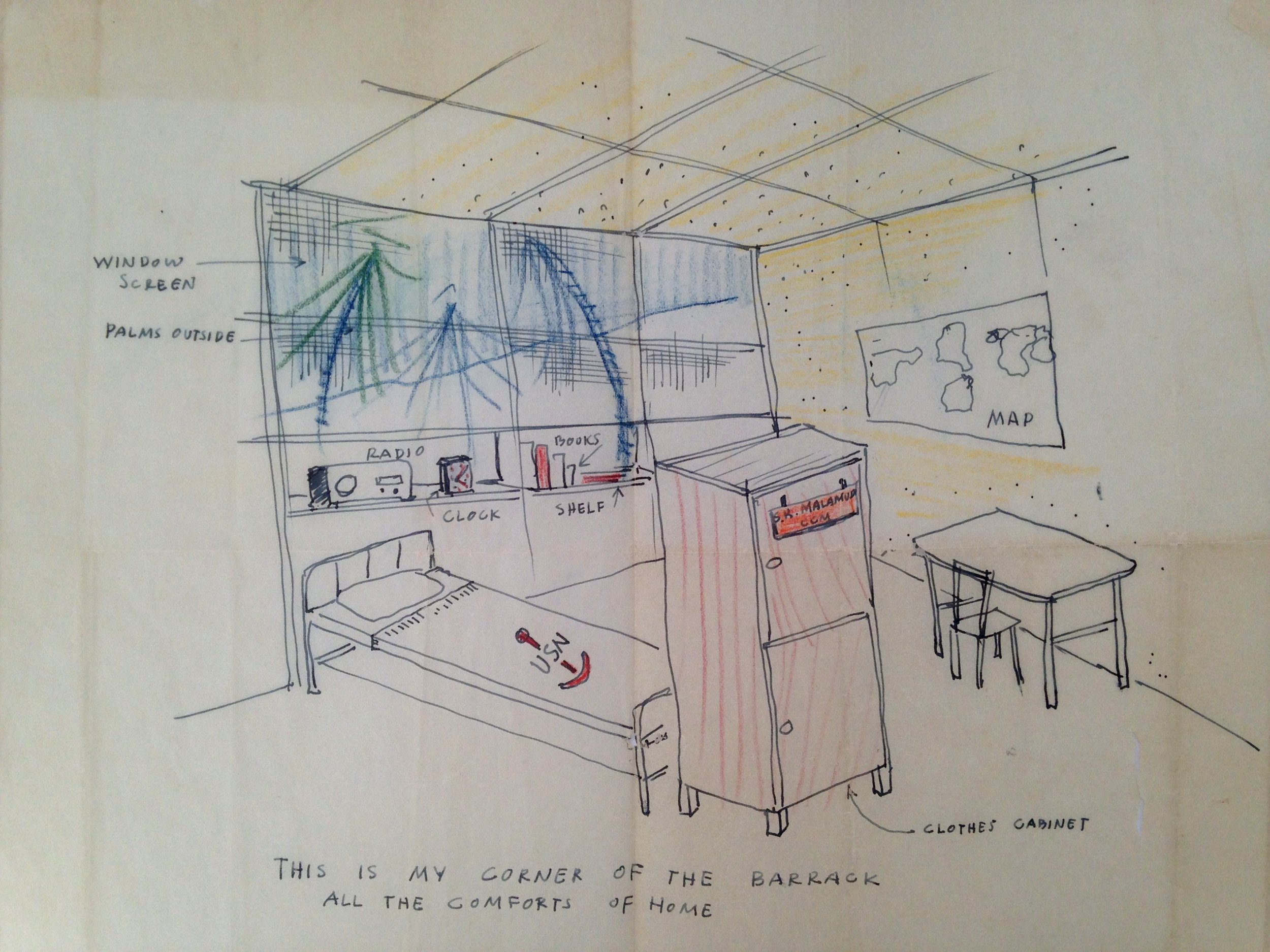

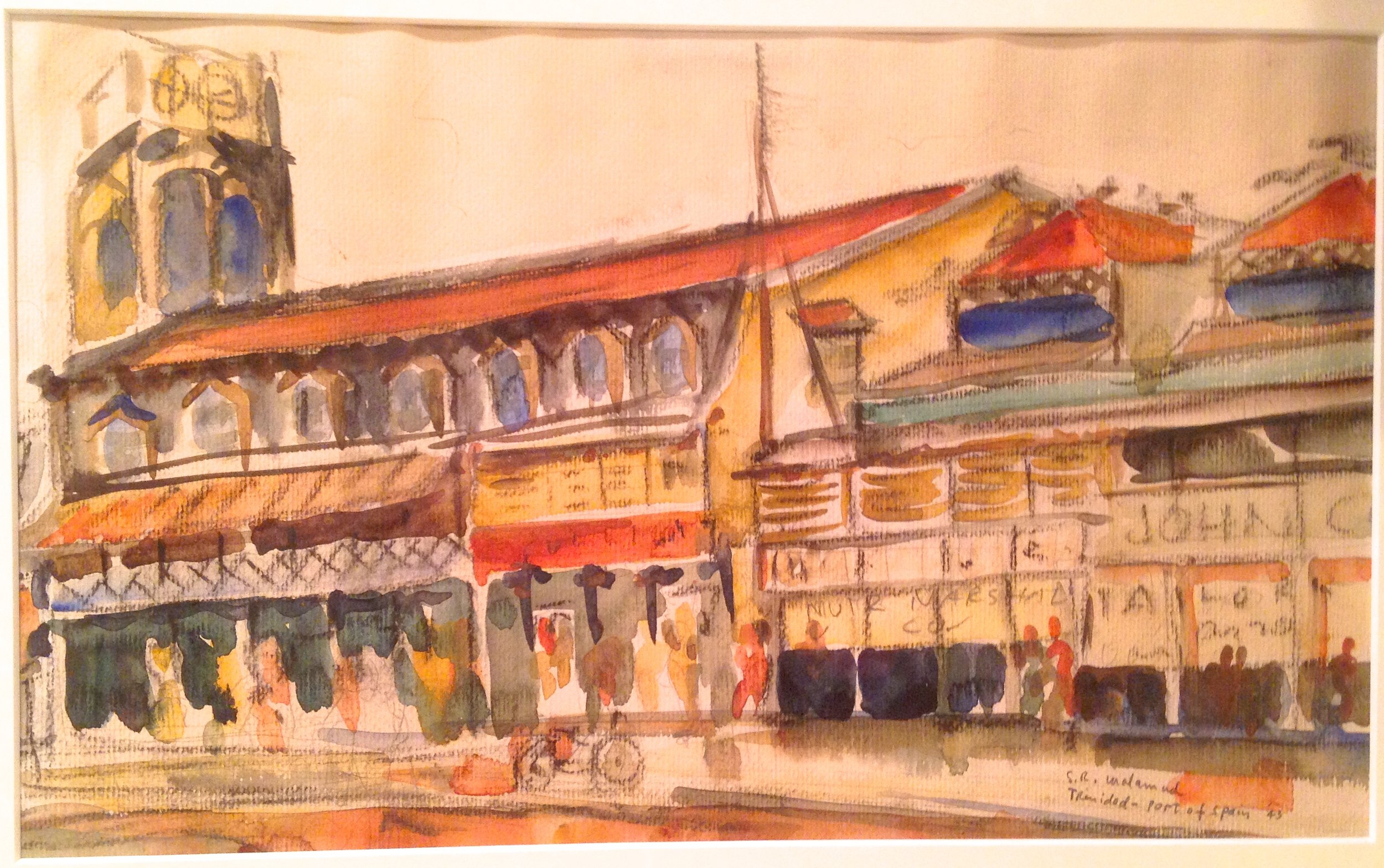

In his free time he painted. He used watercolors and pastels and he did some plein-air work, some documentary, some architectural. Town and street views, shops, local factories, a bauxite mine and refinery, idyllic scenes of fishing boats and palms, his living quarters and bases. His signature surety of line is already there, and it would develop in the urban scenes he painted in the Bronx and Manhattan later in the 1940s and 1950s.

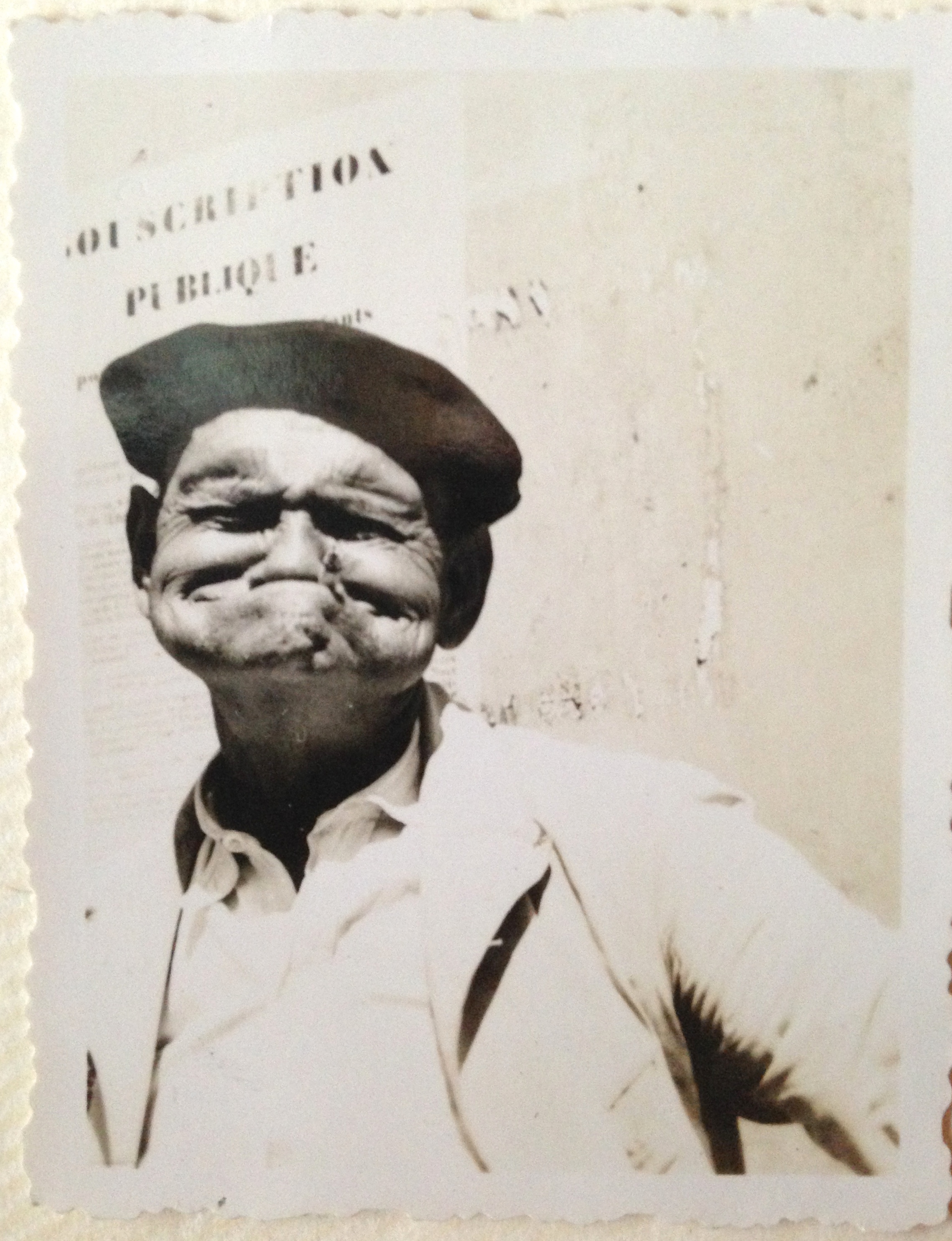

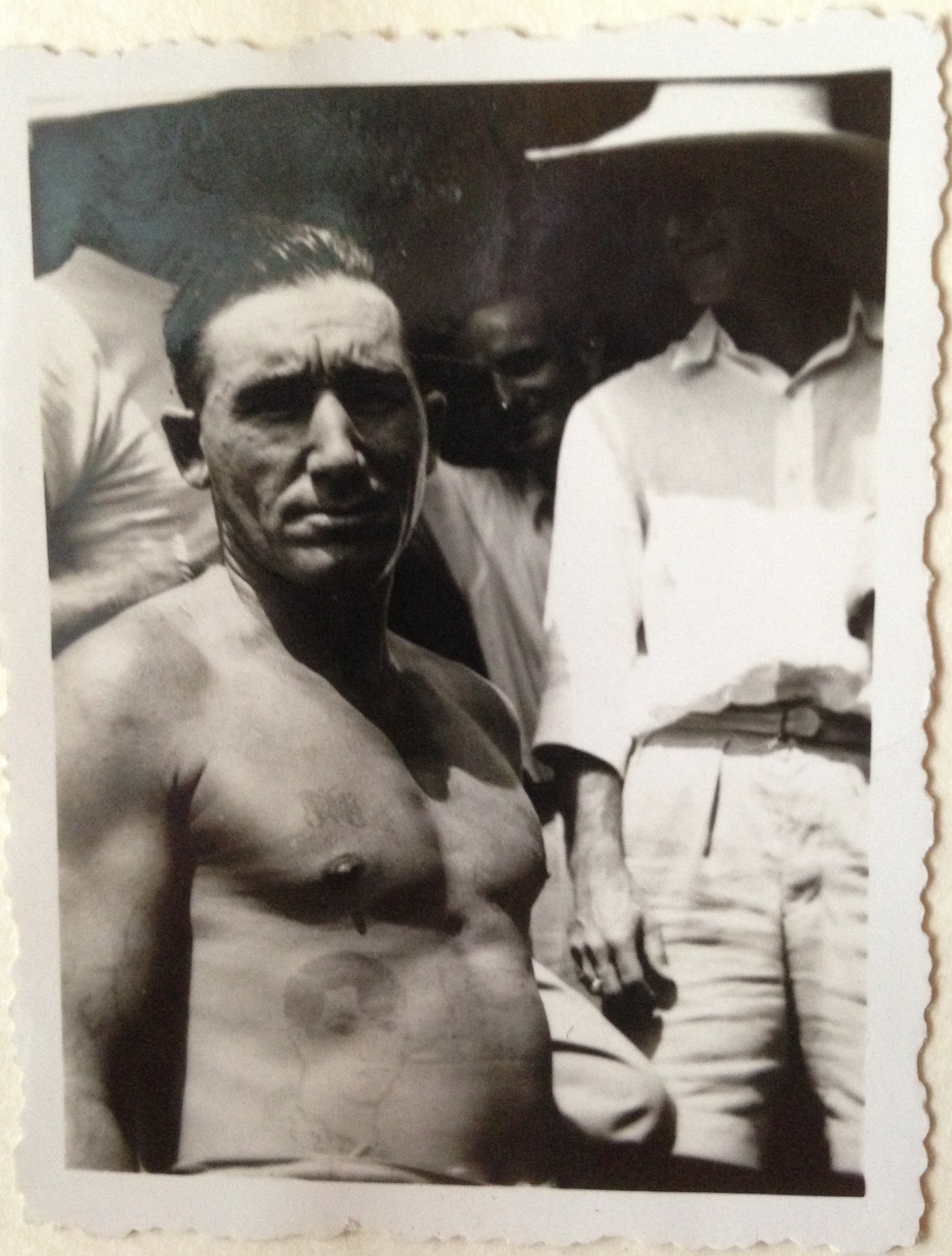

He also took photos and made albums. His quarters, people, colleagues, his friends both in the service and local, nature, views of construction, town and cityscapes, his various outposts, seaside views, jungle views, his prized orchids, and most interesting to me as a kid, many shots of the prisoners and “liberes” from Devil’s Island, who had settled into tragic post-prison lives in Cayenne, the capital city where he was stationed on and off for a couple of years.

When the writer Ernie Pyle visited Cayenne, he wrote of the terrible existence of the so-called liberes, destined to live out the remainder of their lives in squalor, and my father must have thought highly of it because I’ve come across several copies of that essay tucked into various photo albums.

When in Port of Spain, Trinidad, he did an architectural survey of the city. It’s not extensive, but it is meaningful, a rare documentation of the city, a snapshot in time. He drew an annotated map accompanied by 30 or so photos of street scenes and notable buildings, each captioned on the back. One thing he mentioned many times was the dearth of travellers’ infrastructure the region. Most places had none; Port of Spain had one hotel, in the international modernist style. Of course within a couple of decades the entire Caribbean had become a tourist magnet.

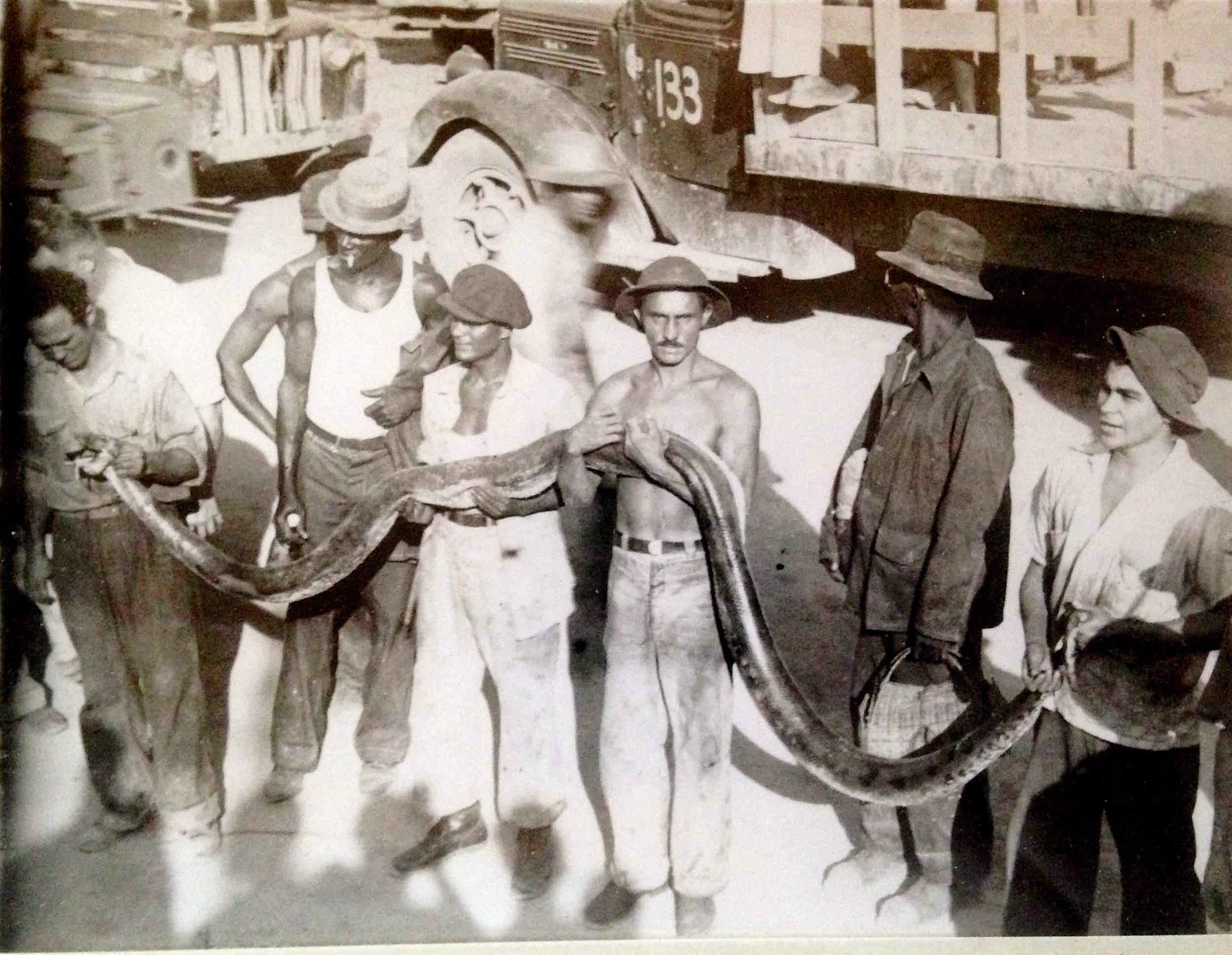

While in the jungle he killed a number of snakes, including a couple of really big ones. One was a 12’ boa constrictor and another (an anaconda?) that must have been 20’ long. He wasn’t a swashbuckler; he ran them over with a Jeep. There’s a picture that exists (I found it!) of about a half dozen locals holding up the bigger one. As for the boa (also found the photo!), he had it skinned and dried, and the snakeskin that he brought back was absolutely the best show-and-tell item ever in the history of elementary school.

He made friends among colleagues, and I remember that we used to get season’s greetings cards from several of them during my childhood, but he spoke more about locals he had befriended. I don’t remember the circumstances but he spent a lot of time with a fellow named Nazim in Trinidad. I think he was a first generation West Indian from the subcontinent. They made excursions around the island and there are photos of them visiting a monastery, eating in various restaurants, and at a Hindu wedding together. When Nazim himself got married, my father was away in French Guiana, but Nazim sent him a roll of photos of the wedding. It must have been a meaningful friendship.

And my father spoke most highly of another friend, an artist/musician/dancer named Boscoe Holder, a man he said was one of the most talented people he had ever met. He spent time with him at his studio and went to see him dance. I remember in the 1960s Boscoe’s brother Geoffrey, a dancer and choreographer, was in NYC and got in touch with my father. I don’t remember if anything came of it, but I remember his being delighted. I just googled both brothers, and wow, he was right about their talent!

All this against the backdrop of a life back home. My father had met, dated, and fallen in love with Jeannette Lubarsky, I think in 1939 or 1940. As was the case with so many people in that generation, war got in the way of love. In the nearly four years my father was gone, I think he was able to return on leave three, or at most, four times, for two weeks at a stretch. I don’t know when they got engaged, but they were married on one of those leaves, on February 6th, 1944. He wasn’t home for good until December 1945. They were married 61 years.