MEMORIES OF MY FATHER ON THE 100th ANNIVERSARY OF HIS BIRTH

March 17, 2018

Having our picture taken. I'm three or four years old, standing on the brick railing outside the entrance to our apartment building in the Bronx. We're both dressed up; my father is wearing a suit and a felt fedora and my pants itch and I'm squirming. He’s holding my upper arm, keeping me steady while my mother snaps the photo.

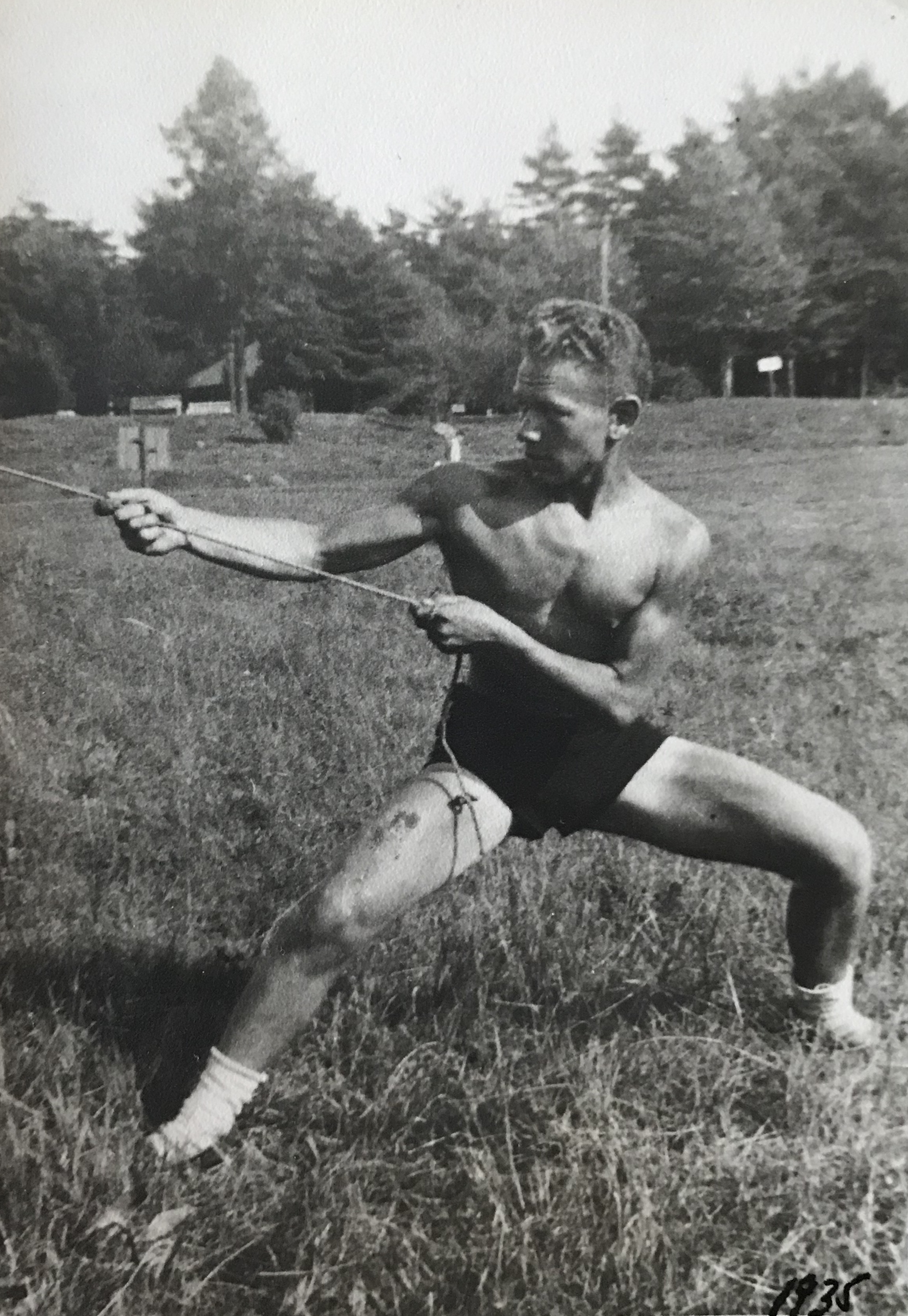

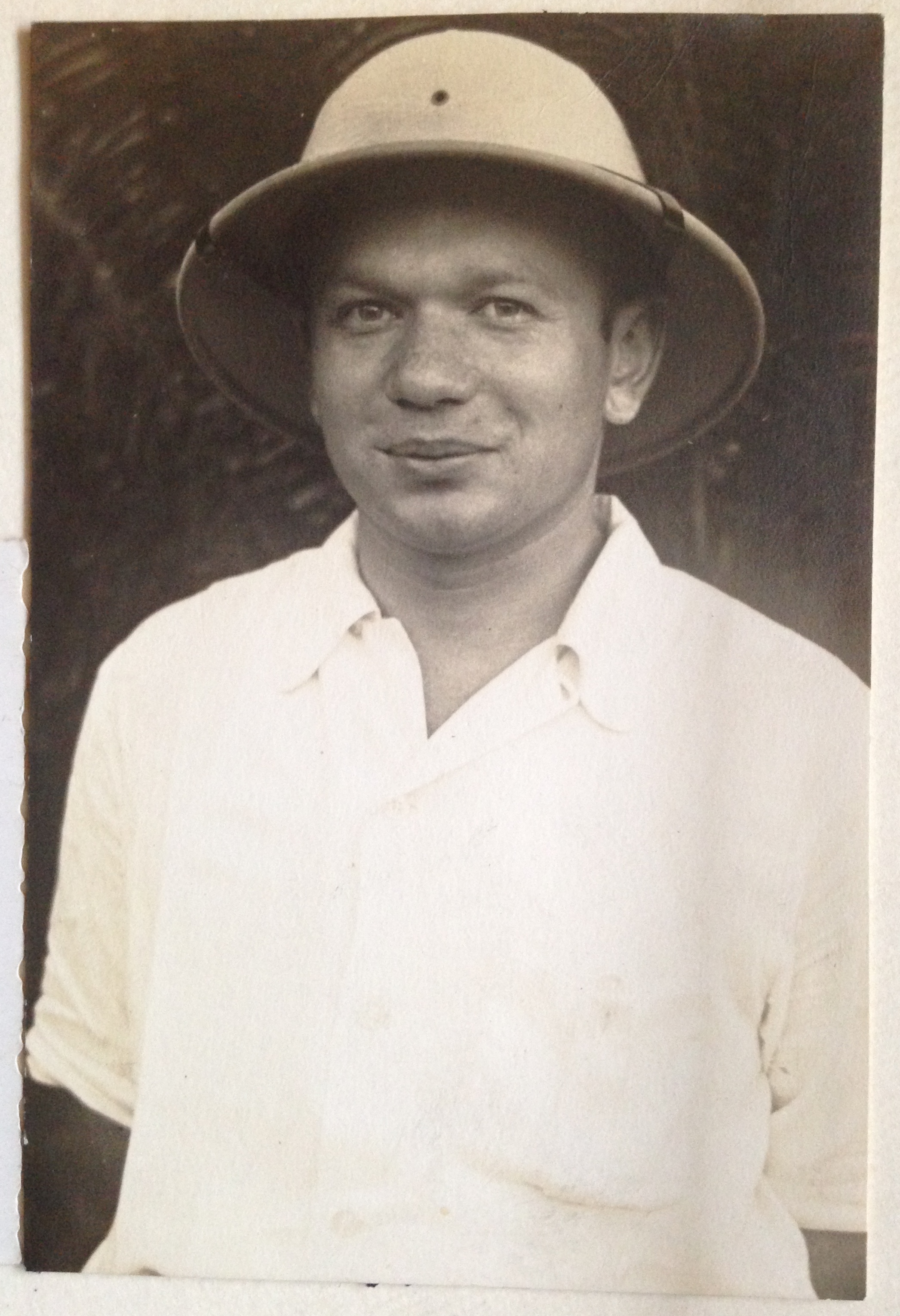

Showing me his stamp albums. I was maybe five years old and very impressionable. He had a special page of stamps from French Guiana with unforgettable images of dugout canoes and young men in loin cloths aiming bows and arrows. French Guiana was one of the places he was stationed during World War II, managing the construction of airbases in the jungle, having just graduated from architecture school.

Waiting for an emergency visit from a doctor at my grandmother’s apartment, my father sitting on the edge of the bed comforting me, which was unusual for him. I had been hit in the solar plexus by an older cousin during an argument over what to watch on TV and I couldn’t catch my breath. To distract and calm me he told me tales of his service in the Caribbean and South America. The story that stuck with the me most was his getting so seasick on a troop ship on the way to Trinidad in the middle of a storm that he said it was the only time he ever wanted to die.

His snake skin. When he was in French Guiana he killed two huge jungle snakes by running them over with a Jeep, and he had one of them, a boa constrictor, skinned as a memento. The second snake was an anaconda, black and much larger, and he had a photo of seven brawny local men holding it up for the camera. The boa constrictor skin was large and colorful and needed about a half dozen elementary school kids to unfurl it. I was the star of show-and-tell from first through fifth grades. It was possibly the best show-and-tell in history.

Driving on a residential street somewhere in New Jersey in our new 1961 Mercury Monterey on our way to visit relatives, Bruce and me in the back seat. My father slowed down while looking to his left and said "Did you see that doorknob?" I started to say something, but my mother interrupted and said “Sam keep your eyes on the road!”

Visiting my father's office in NYC during summer vacation when I was around ten years old. It must have been during school vacation; I had been to his office for brief weekend visits before, but never for a whole day of work. At Grand Central Station we bought corn muffins and he told me he got one every day on the way to the office. Walking uptown I had to run to keep up with him. It was about 15 blocks to his office on Sixth Avenue at 54th Street and I was thankful for red lights because I could finally catch my breath. His office was on the 33rd floor of a 34 story building with knee to ceiling glass windows overlooking the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art. For a while I sat (in my mind, bravely) on the ledge right next to the window and it was vertiginous but super exciting. But my most vivid memory of that day is how fast he moved and how hard he worked, virtually never slowing down.

My father painting at home. He had carved out a piece of our small basement for a workshop, and an adjacent part for painting. I was always struck at how deft his movements were, swift and sure. It looked like he was pushing paint around haphazardly and then it magically turned into something. When I was young I took it for granted. When I started to paint seriously when I was 12 or 13 I was awed and jealous. I still am.

Showing me his portfolio of hundreds of drawings he had been required to make as an an architecture student, sketching famous and not-so-famous buildings and structures around the world. He had drawn images of Greek and Roman temples, Italian Renaissance and Baroque churches, and 19th and 20th century modernist buildings. His line was strong and certain and unquestioning. Curiously he had razored out the grades he got on each work and I wondered why; they all looked like A work to me. I still have them.

Teaching me how to sharpen a drawing pencil. He used a flat, wide wooden pencil, and rather than sharpen it to a point, he showed me how to sharpen it to a wedge so that one could vary the thickness of the line while drawing. It was my first time using a single-edge razor blade.

Bringing home a salvaged piece of finished hardwood thrown out from a job site to use as a display mount for an award he'd gotten in architecture school: Best Draughtsman of the NYU Class of 1940. He wasn't boastful in any way at all, but he was proud of that medal.

In my sophomore year of college, I got a really good pair of lined leather winter boots. But I lived with a friend's Belgian shepherd puppy who one night ate the top of my boot. During Christmas break my father somehow found some leather and repaired it with a heavy needle and thick coated thread. This was in December of 1972. I still have those boots and went out in the snow in them this past winter.

Seeing my father doing inspection tours at the partially built One Astor Plaza on Broadway while I was working there as a union laborer during my college breaks. We workers were dust covered and filthy and my father would come by dapperly dressed in suit and tie and hat, rolled up blueprints in hand, and everyone would stop working and there would be silence. The managers were respectful and deferential, but I could sense in my fellow low-level workers a combination of respect, resentment, and disdain.

When I was preparing to leave for my 8 month trip along the Central Asian silk route in 1973-1974, my father exercised what must have been painful restraint, given how much he worried about me and my brother. My mother pleaded with me not to go, over and over; my father hated the idea of my going but I think he realized I was going no matter what he said.

Visiting us when we lived in the San Francisco Bay Area. We took a trip to Big Sur and were driving up Route One back to SF when we stopped to admire the view and take photos. My father quickly did a drawing on the spot with markers, of the cliffs meeting the ocean at a turn in the road. It reminded me of a very good John Marin, whom he admired.

Telling a joke. He was usually terrible at it, getting the timing wrong, forgetting critical segments. But he would start giggling while he told it and it was infectious; often everyone would end up laughing.

My father was a terrific photographer. But he had a habit that became one of our family’s signature jokes. Whenever he’d arrange a group portrait, he’d aim and focus and say “one...two...oh wait one second, you move a little to the right, now one... two...oh wait, let me get a different angle, ok one...two....” This could go on for minutes.

A few years after we moved into our house in White Plains in 1958, my father turned a large second story deck into an enclosed porch, doing everything himself. Over the years he made improvements, more permanence, a new roof, and it essentially became an extension of our kitchen. Many years later when we were visiting, when he was in his early seventies and still working full-time, he was climbing on the roof, one foot in mid-air, hanging on to a protruding piece of wood with one hand and hammering with the other. My mother was screaming for him to get down, and eventually we were too.

He was the most devoted son I've ever known. He was unusually close to his mother, perhaps having to do with hanging on to her while walking across Eastern Europe as a toddler fleeing horrific pogroms in the wake of the Russian revolution. When she was still young and healthy he spoke to her every night, and in her later years when she was sick and uncertain, he would speak to her four or five times a day, and visit a couple of times a week. He would excuse himself from meetings to call her. It was the source of some jealousy between my mother and his.

For the nearly three decades that I worked as a full-time book dealer I traveled extensively, both domestically and overseas, a couple of hundred week-long or longer trips while he was still alive. I'd call my parents to say goodbye every time I left and my father would say the same thing, every single time: "Don't forget to have a good time. It's later than you think!" It became a family joke and personal motto. And then when I'd return, we'd do a sort of Abbott and Costello routine. He'd ask "How'd you find the kids when you got home?" (meaning had they changed much?), and I'd respond "It was easy, I just looked in their rooms." As corny as could be but he giggled with delight just about every time I said it.

Taking a day trip to Yale University when Terry and I were visiting from California circa 1980. We visited the Art Museum and the Beinecke Library and had a nice lunch. It was a wonderful day and I remember sitting in the back seat of the car on the way back to the house wishing I could freeze time.

The sparkle in his eye and the joy he took in Terry's signature walnut pie, year after year after year.

My father eating hot dogs with eight year old Josh, living with difficulty in an assisted living apartment. Josh was always patient and graceful with him, and my father always perked up when he came to visit.

My having to sign documents and checks for him because his hand, which had been so sure, was shaking so violently from Parkinson's.

Suffering from dementia in his final year, forgetting that my mother--his wife of 61 years--had died a few months earlier, desperate because he didn't know why she wasn't in bed and where had she gone?