MY MOST UNEXPECTED (AND PERHAPS BEST) BOOKSELLING STORY

I had a really good bookselling story relatively early in my career. The only downside to it was that I figured that no matter how long I worked, I'd probably never have a better one.

In January 1992 we received a catalogue for a major art book auction at Sotheby's in London. They were selling the library of a famous art historian, Alfred Scharf, a German Jewish scholar who escaped Germany in the early 1930s and spent the rest of his career in Great Britain. Scharf specialized in old master painting and wrote a definitive work on the Italian painter Fra Filippo Lippi. He amassed a major library of both reference works and rare books on everything from the ancient world to early 20th century art, at a time when prices of rare and important books were still reasonable and within the reach of a successful university professor, an impossibility today. After glancing at the auction catalogue we decided we should attend and that I'd be the one who would go.

The library was immense, broad and important. In most catalogues from major auction houses books are listed individually, each lot representing a single book. But Scharf's library was so large that even scarce and expensive books were listed in group lots. Many of the lot entries in this auction catalogue listed several books with bibliographical information accompanied by the phrase "and others". Some listed just a couple of books, others 5 or 6, but the "others" ranged from a couple to 30 or 40.

I had been working full time as a bookseller for a little under 5 years (almost a decade part-time before that) and I was finally starting to find my footing. I attacked the catalogue with gusto. Prior to the internet, determining the values of books was a much more opaque and difficult task, but we had tremendous resources at our office. We had a card catalogue with a record of every book we had sold since the 1940s, and walls of shelves of dealer catalogues. I spent several days systematically going through the titles listed in the catalogue, determining approximately what price we could sell them for and how much we could pay for them. My notes were extensive and by the time I left for London I had determined the value of all the listed books in which we might be interested, but there was still the big mystery: What about all those books listed as "others"?

So that was to be my job when I got to London. I would go through the 10 or 20 or 30 "others" in each lot and try to determine their value and adjust our bids accordingly. Since there were over a thousand lots in the auction, I had reserved two full days to preview the auction and make further notes.

When I got to the auction house that first morning, it was a very civilized mob scene. Tweed-jacketed dealers from all over the world were shoulder to shoulder, jostling to pull books off the shelves in the multi-room preview section of Sotheby's. I quickly became aware how expert the Sotheby's staff was. In virtually every case, the books listed with bibliographical information turned out to be the only valuable books in each lot. The three or four listed books would be worth hundreds or thousands of dollars, but the "34 others" were all toss-ins, worth 10 or 20 bucks a piece, unimportant books that we typically wouldn't be interested in and that would hardly be worth the cost of the postage to send them back to the States. This happened in lot after lot after lot. They had it down--the listed books were all valuable and the "others" weren't. In two full days of working non-stop, I didn't find a single "sleeper", a treasure that might have been buried among the "others".

At the very end of the catalogue was an entry that listed two books and "3 others". The problem was these books were immense and unwieldy and the crowd was still so thick that it made it almost impossible to pull them out to view. So I didn't. After all that work--several days in the office and two days on site--I figured I didn't have to look at that lot, I could just assume that the "others" were not valuable and that I'd base my bid on that lot on the two listed titles and forget about the others.

The auction went well for us. Though we were outbid on many important titles, we still got dozens of lots that we knew we could sell at a profit, and I was pleased. I got that last lot, the one in which I hadn't seen the "others". I figured we could sell the the two listed books for around $1000, so when the opening bid was around $400 I put my hand up. I was the only bidder.

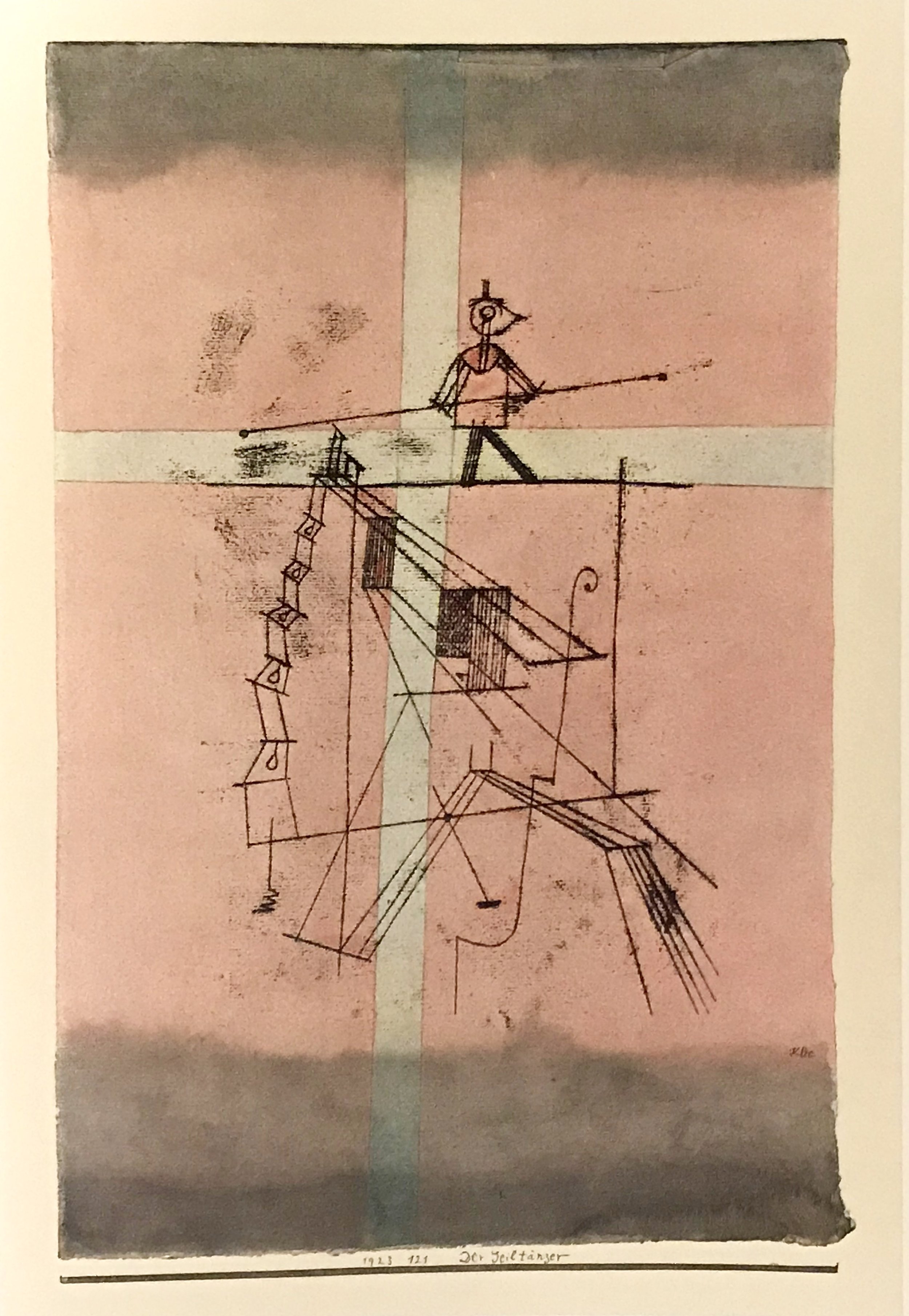

Around six weeks later the shipment arrived and we unpacked box after box after box, happy with what we had bought. When we came to the final lot, we knew the two books I bid on were good, but of course we took a look at the three "others". Two of them were virtually worthless--one of them was even missing plates--but the third one seemed curious. It was a large folio portfolio entitled "Kunst der Gegenwart" (Art of Today) published in Germany in 1923. There were forty elegantly matted reproductions of avant garde art works from the 1910s and 1920s, but then we came to a few things that were more interesting. As we examined them, it became clear that five additional images were original prints, and that the signatures were real. A couple of the prints were by second-tier German Expressionist artists, but there was a signed etching by the important German Impressionist Lovis Corinth, a signed woodcut portrait by Max Beckmann, and most importantly, a signed color lithograph by Paul Klee, "Die Seiltanzer" (The Tightrope Walker). The Klee is an iconic image, one that he did in oil, watercolor, and print form.

We looked up auction records. 1992 was a curious time in the art market and auction records, though still the best indicator of relative value, were a bit misleading just then. The art biz was in a major slump at that time, mostly due to the recent crash of the Japanese stock market. During the 1980s the Japanese economy had soared, creating an unsustainable bubble. The Japanese were buying Van Goghs and Renoirs for tens of millions of dollars and stashing them in bank vaults, and when I first visited Tokyo in 1988 it felt like the crowds in the department stores were in a feeding frenzy. But by 1992 the bubble had burst and prices for blue chip art had declined, so the auction records had to be viewed with some hesitation.

That said, the Corinth had appeared several times in the 1980s, achieving between $1500 and $2500. The Beckmann had also appeared a few times, selling for $5000-8000. But we had to blink our eyes when we found that the Klee print had appeared around a half dozen times in the previous decade and had sold for between $31,000 and $93,000. Even if the highest prices weren't justified in the current market, we had somehow acquired a very valuable work. And it was complete, a real rarity.

We put a price on the portfolio that took into consideration both the auction records and the fact that the market was in a slump. Over the next few months we came close to finding a buyer several times, but each time the deal fell through. Finally after about 18 months we were connected to a dealer from England who specialized in German Expressionist art. He made an offer somewhat lower than what we were asking and we agreed to it but we insisted that given the size of the discount we would accept only cash. Though he was a bit disgruntled by our terms--he would have to fly from London to New York to hand deliver the cash and retrieve the portfolio--he agreed to them. I believe he already had a buyer for it.

A few days later I found myself sitting in a basement bank vault in Manhattan counting stacks of crisp new $100 bills while the buyer was collating the portfolio, checking the signatures and the authenticity of the piece. It felt a little like out of a James Bond movie from the 60s. The dealer had arrived from London that morning, we were making the handoff in the bank vault, and he was flying back that evening. I put the stacks of cash in my briefcase and headed back to the office, nervous about carrying so much money on me. Weirdly, the strongest memory I have of that interaction was how terrible the guy's breath was in the tight, airless bank vault.

Bottom line: Sotheby's blew it big time and we were the benefactors of their mistake. In a major auction with thousands of important and rare books, meticulously catalogued with great skill, care, and expertise, and attended by a large crowd of international dealers, perhaps the single most valuable book in the auction went unnoticed. By everyone. Sotheby's cataloguers missed it and not a single bookseller pulled it off the shelf. Anyone knowledgable who had looked closely at the book would have realized that it was something quite extraordinary. And we got it for free.

The only negative was that while I was driving back to the office I realized even if I stuck with this career for many years (which I did) I'd probably never have another story as good as this one (which I don't).